So I'd like to have a fresh start going into the New Year, beginning to be more focused on doing my journal when I want to, and trying to put an end to the constant procrastination. New Year is a special time in Japan, so I'll tell you a little about that first.

One of the most important and favourite holidays, the New Year, or Shōgatsu, while having many similarities to the celebrations in America, also have some traditional and religious connotations that come into the mix as well.

New Year's Eve is called Ōmisoka, referring to the last day of the year. At this time, the usual fare is to send New Year cards to family, friends, and even colleagues at work or school. Much like Christmas cards in America, which are still sent during Christmas time in Japan, New Year cards tie up loose ends, giving greetings to loved ones or checking in with those you haven't spoken to in a while. It's always exciting to get the mail and see all of the decorative cards, especially since kids get money in them from family and friends of their parents. Of course, it's also fun to count down to the New Year, have champagne, and watch really cheesy family-friendly music performance New Year specials on TV. Another custom similar to American New Year customs is the eating of special food. Certain traditional or regional foods are enjoyed on New Year's Eve and then on New Year's Day that represent a healthy start and prosperous year, good luck, or just the taste of a certain type of food that one looks forward to each year around this time. Popular fare across the country include making or having mochi, or a type of noodle, specifically udon or soba, which are called "toshi-koshi" style, referring to the custom of eating long noodles to bring you through with long luck into the New Year.

There is also a popular platter of traditional New Year foods representing certain "good luck" wishes, many of the foods chosen to express a sort of pun for an auspicious year, or in specific colours or patterns to represent something wanted in the next year, for example, circular red fish cakes representing the rising sun, or eating soybeans, since the word for bean, mame, can also mean health, or good health in the New Year. These dishes are made into a huge platter or meal over several days, since cooking during the first few days of the New Year is bad luck. Traditionally, these holidays would require the large meals to be cooked for the celebration, or o-sechi, but now it is a tradition to make these foods, called osechi-ryōri, or purchase them. It's very intimidating to go by shops getting ready for New Year, or even popular convenience stores (my favourite places to go because of the vast selection of great bad food to be found) to avoid becoming extremely hungry when every window is offering varying levels of expensive tiered platters of osechi-ryōri.

Yummmmm. And only 320 dollars...

Please read more about the origins and the specific foods and what they represent here.

There are also many games traditionally played around New Year. If you watch Kagrra, no Su, Kagrra,'s web show, you may have wondered why the hell they had top-spinning, cup-and-ball challenge (kendama), card games, or shuttlecock competitions (hanetsuki).

These are popular games that were traditionally played, and nowadays are enjoyed by children, New Year merrymakers, or traditional people like Kagrra,. Other popular activities include flying festive kites, playing suguroku, and making New Year decorations with mochi, tangerines or oranges, and pine boughs.

Here you can see Kagrra, vocalist Isshi slapping a traditional kadomatsu with his hagoita.

Popular religious celebration includes decorating your home with sacred objects made of rope and straw, and Buddhist temples will ring a ceremonial bell one-hundred and eight times to signify the New Year and to release people of one-hundred and eight earthly desires, cleansing you for the New Year with one dispelled by each ring. Shrines will be visited, often hosting some of the festivities and giving out amazake, a traditional sake-style drink that is sweeter and less alcoholic. Special words are given for many of the things done in preparation for the New Year, with poetic words signifying a "first" special event to experience that year that you take note of. Cleansing the house to start fresh for the year is a custom for the toshigami to arrive and visit your home, gods or ancestors that bring the New Year with them.

Also during cleaning time, the real fun starts. So let me tell you a little bit about yōkai.

The team yōkai can refer to several things, including ghosts, monsters, evil objects, demons, or anything of that nature. It is a general term for some sort of supernatural creature or spirit. I will go into this more in my next yōkai entry. The ones we will focus on today will be referring to the evil objects, and a certain New Year's beast.

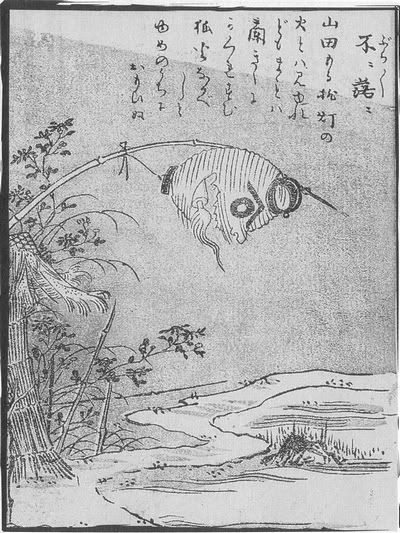

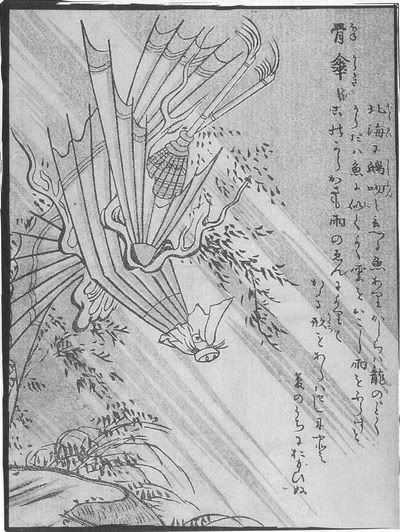

The most common yōkai you may encounter would be the tsukumogami (付喪神). These are "artifact spirits", or a type of man-made object that has been possessed by a wandering or malicious spirit. If you remember the chōchinobake entry, some of the most common examples of tsukumogami in media and art include the haunted lantern spirit, umbrella spirit, or a tea-kettle spirit.

They are all depicted here in these illustrations by Toriyama Sekien.

The ritual New Year's cleaning is called susuharai, and this is meant to cleanse and protect one's belongings from becoming a tsukumogami. Tsukumogami itself is a play on words, something that you will begin to see much more of if you continue to learn about different types of yōkai. It basically means "a spirit possessing a ninety-nine year old object". Ninety-nine, in this case, merely refers to "a long time", and not literally ninety-nine years, but the general agreement is that, if left to its own devices for around ninety-nine years, an object that has spent a lot of time with humans and has since been forgotten, mistreated or thrown away without a proper "burial" (cleansing) will morph or evolve in order to allow an evil spirit or lost soul to take over it and help it get revenge for being cast aside after such faithful service. Another similar ritual, ningyou-kuyo, is a cleansing for beloved dolls and toys, and will be further explained in an upcoming entry.

Anyway, susuharai is the ritual year-end cleaning that I mentioned, but in honour of the much-used or older objects in the home. As you clean your home and make sure that everything is in proper working order and fresh and ready for a new year to start as well, this will not only ready your home and possessions to continue to prosper and serve you with good luck, but also to make sure that any object with the capability to become a tsukumogami feels remembered and treated properly. A very famous story about the tsukumogami relates to the Hyakkiyakou, the demon's parade, in that when all the demons advanced on the Heian capital, many discarded objects joined them, having become tsukumogami and sworn revenge on those who hurt them.

Around this time, many items that were no longer used had been re-discovered during the susuharai, and they were cast out into an alleyway or thrown in the trash.

The objects, furious at how disrespectfully they had been treated after being created and serving their purposes so faithfully, became animated, or even repositories for lost human souls, and swore vengeance on their former masters who no longer wanted them.

Ever since the tsukumogami marched on the capital, the susuharai ritual also makes sure to properly cleanse and display items no longer in use so that they can join the new year with no ill will.

The last yōkai I will discuss today is the dreaded namahage (生剥). This is your beastly, monstrous type of yōkai, a supernatural creature that is a specific species of yōkai, instead of something normal that was turned into one.

The story of the namahage (and most of the festivals involving him) originate in Akita prefecture, which is in northern Japan. The tale goes something like this: A fisherman from Akita went to China, bringing back with him several namahage. Being rather oni-like (oni referring to a type of demon), these creatures were extremely strong and worked with the people, helping them with their heavy-duty work for several months. However, on New Year's Eve, the namahage rebelled against the people and took over one of the farming villages, claiming it as their own and terrorizing the inhabitants until they left. The farmers then came up with a plan, that they would give the namahage the village if they could do a task, the task of laying one thousand stone steps up the mountain to their shrine in one night. The namahage readily agreed, and set to work. Well before dawn, the villagers came to check on the progress and were horrified to see that the namahage had already laid 999 of the steps. Thinking fast, a clever farmer crowed like a rooster, making the namahage believe that it was dawn. Defeated, the namahage kept their promise to return to China, but came back every year on New Year's Eve to terrorize the village.

In Akita prefecture, the namahage celebration is a huge tourist attraction, where the shrine will play the namahage-daiko, the namahage drum, while the "namahage" will return and put on a performance for everyone.

Whether or not you live near the shrine, many people in Akita, or even people nationwide, will still dress as namahage on New Year's Eve and storm their village or neighborhood. Namahage literally means "scab-peeler", and refers to another legend that the namahage, like a trick-or-treater, will arrive on a certain night looking for ill-behaved children. Traditionally, children who were lazy would hang out by the brazier all winter long instead of working, and would develop scabs on their skin from being so close to the heat. The namahage would arrive and look for these delinquent children, and forcefully rip the scabs right from their skin. Now, people dressed as namahage will show up at people's houses and ask if there are any naughty or crybaby children living in the home, or even do it as a joke to a new neighbor or young newlyweds to "initiate" them into the community in a fun way. When the namahage arrives and calls for bad children to come out into the snow and have their scabs ripped off, your parents will ask you if you're being good, and if you promise you're not a lazy crybaby child, they will tell the namahage that no ill-mannered children are there, and to go to another house. Naturally, the sight of a namahage usually makes a normally well-behaved child cry even more, but later on in the year if you're being bad or whiny, your parents will remind you about the namahage coming, and that they'll tell him you were bad if you don't stop.

In places where many namahage annually run around, those dressed as namahage will storm into a home, wailing and moaning eerily "wooooooaaaahhhh", and dance around, playing their personal namahage-daiko until the head of the household gives them sake, amazake, mochi, or whatever traditional favourites the family is cooking. He will then pay respects to the family and their kamidana, leave happily, and not return to terrorize the house.

Of course, this can often go very wrong. Every time around New Year, the news programs will talk about the namahage legend, and what the local community or the Namahage Festival in Akita is looking like as they prepare for the celebration. Unfortunately, some folks get into mischeif, and one year, a man dressed as a namahage got drunk, broke into the women's public bath, and molested several ladies there. Reports of the scandal ran rampant, including such juicy details as the women running away screaming, or that the namahage had openly groped several womens' breasts.

So not just children need be frightened of the dreaded namahage.

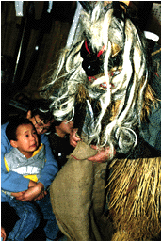

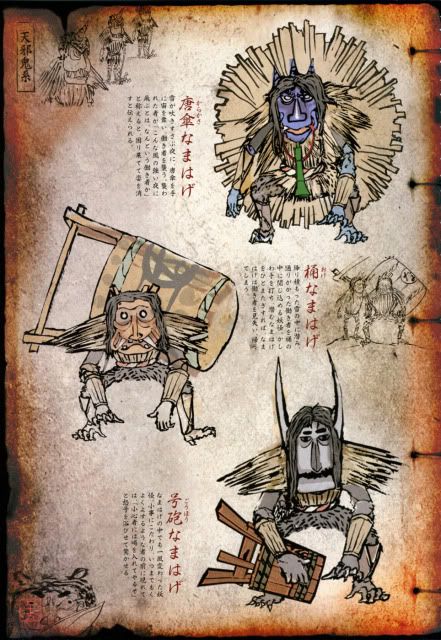

Here's what you need to know about how to recognize a namahage.

Their faces will be oni masks, the blue one representing a female, red representing male. The female will carry a wooden bucket and knife, hitting the bucket with the knife to make her own personal namahage drum. The male carries a wooden staff with paper streamers attached, which he shakes around as he dances to the drum beat and wails at people. They both wear straw raincoats, traditionally associated with the tribal people of the Akita prefecture and Tōhoku region.

The namahage also appear as demon encounters in the video game Ōkami. Fittingly enough, they appear once you reach the Northern Lands.

Basically, those are the main points of interest during New Year in Japan. Hopefully you enjoyed it and might even include some of these customs in your own New Year celebrations! Thanks a lot for reading, and please look forward to my next entry, and the continuation of my yōkai series! Have a Happy New Year!!!!

No comments:

Post a Comment