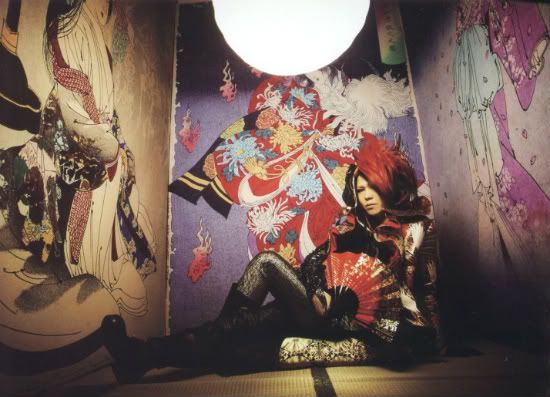

Today, let's take a look at the photo on the right.

This girl is 小町桜の精, Komachi-zakura no Sei, the Spirit of Komachi's Cherry Tree.

If you read my last entry, you will hopefully be thinking to yourself, "Hey, that's an Oiran!" Why thank you for noticing, I feel a deep sense of accomplishment. Yes, you can tell by her headdress and obi that she is a high-ranking courtesan, but the soft colours of her kimono and the... lack of feet establishes her as the aforementioned Komachi-zakura no Sei.

But who is that?

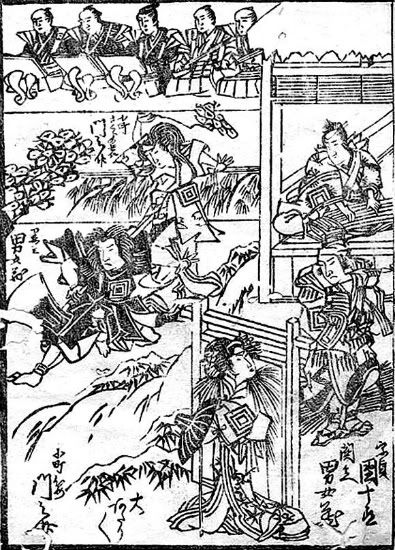

In fact, she is a famous character from a kabuki, Tsumoru Koi Yuki no Seki no To, the dance of which, Juuni Hitoe Komachi-zakura, is quite popular.

Let's have a little history of this kabuki, and then I'll tell you the story.

Tsumoru Koi Yuki no Seki no To, best known simply as Seki no To, was originally produced to show off the kabuki theatre, featuring a stunning array of sets, costumes, romantic drama, and supernatural action.

That sounds a lot like a Kagrra, show, right? And the soft colours of her kimono, coupled with the flamboyant style of her accessories, in which she languidly poses, cherry blossoms flying all around her, seems to fit in well with the Kagrra, aesthetic. But in fact, the story has a lot more significance to Kagrra, and in particular Isshi and his writing than even that!

The cast of characters in the kabuki, well-known from the drama in which the tale originates, are completely adjusted simply to be dramatic and unearthly. And after the initial performance of the dance-drama, the drama part of it was completely abandoned, and only the grand finale at the end, which still is considerably longer than most dance numbers in kabuki, is the only part that remains. So when people say Seki no To, they mean Juuni Hitoe Komachi-zakura.

Obviously, there are many different variations on the performance of it, but most follow the same basic story.

A noble sits playing his koto, while his gatekeeper drinks sake and lounges under a cherry tree in full bloom. The noble, by the name of Yoshimine no Munesada...

Let's stop.

Yoshimine no Munesada (良岑宗貞), later known as Henjō, was a waka poet (waka is a style of classical Japanese poetry) and Buddhist monk from the Heian period. And who loves Buddhism, traditional poetry, and the Heian period? Why, Isshi does! So our kabuki is purposefully referencing Heian poets and aristocracy, despite the popularity at the time to reference more contemporary work, solely to stand out and be given free reign to capitalise on the Heian ideal of beauty, excess, and enormous, complicated, trite metaphorical set pieces for the entertainment of the audience and in particular, themselves.

Why does that sound so familiar to me?

Henjō is considered to be one of the best poets of Japanese verse, finding himself ranked among the 36 greatest poets of ancient Japan, as well as the 6 greatest waka poets of the Heian period.

Perhaps the most well-known of them all is Ono no Komachi (小野 小町).

Ono no Komachi represents to most what you think of when you think of waka poetry, the Heian period, and beauty. I've mentioned the Heian cult of beauty and significance of female writers of the time before, but I purposefully left out Ono no Komachi, because she deserves a bit more explanation.

Ono no Komachi was apparently so amazingly beautiful, that she is cited as the ideal of appearance, even though the exact appearance is lost in time. Female writers give us most of the information we have on the Heian period, and they didn't like to be specific about what parts of each other they found so beautiful. But Ono no Komachi was notoriously well-known for her exquisite looks.

I say notorious, because, long after the Heian period, she was featured heavily in Noh and kabuki, not as a beauty, but as an ugly old crone. She wanders the countryside, no longer admired and sought after by the very public and prevalent rumours of her affairs at the time. She is simply alone, and has nothing, and regrets her youthful life of lust and appearance, begging for money and musing on nature and poetry.

Obviously, this role is given to her long after the Heian period, when Buddhism was the predominant religion of Japan, and the opinion on the former world of excess, beauty, and self-love was profane in the eyes of the Buddha, and she serves as a morality allegory.

However, her poetry is still prized, regardless of the later thoughts. Ono no Komachi and Henjō's poetry are featured in an anthology by Fujiwara no Teika, 100 Poems by 100 Poets (百人一首), several examples of which were used as art during Isshi's solo from the Miyako concert.

See? See how it all comes together?

While these two famous poets' works are not among those used in the song, I would like to share Ono no Komachi's piece.

花の色は

うつりにけりな

いたづらに

我が身世にふる

ながめせしまに

The flower's colour

Has already faded away,

While in idle thoughts

My life passes vainly by,

As I watch the long rains fall.

I think that Ono no Komachi has greatly influenced Isshi.

But back to the kabuki.

Since we are now in a topsy-turvy world where excess is OK again, a pre-monk Yoshimine no Munesada sits playing his koto. And who would walk up to his gate but one Ono no Komachi herself!

Oh, didn't I mention that one of her many, many rumoured love affairs was with Munesada? Yes, so she appears in all of her exquisite Heian glory.

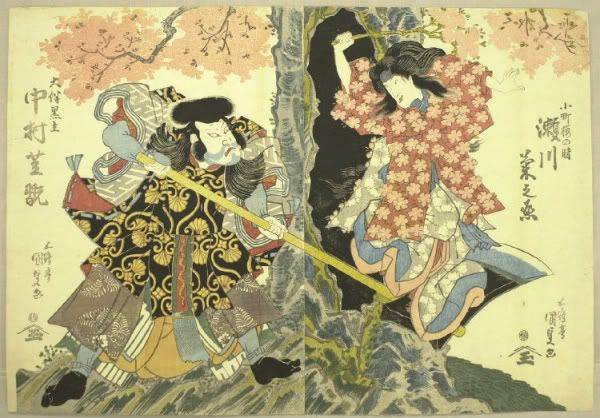

The gatekeeper, Sekibei, is drunk off his gourd and refuses to let Ono no Komachi, here Munesada's fiancée, in to see him, but Munesada sees her and they share a passionate moment. They recite love poetry to one another, and are altogether too sweet for Sekibei's taste, and in a drunken rage he rants and raves on court gossip, and sways this way and that in his stupor, spilling from his robe pocket several imperial seals which he has stolen and clearly intends to use to his own advantage. Ono no Komachi understands the situation right away and takes one as evidence.

It is then that a letter arrives, containing the bloodstained sleeve of Munesada's brother, Yasusada. Munesada realises that his brother must have been killed by the gangster Ōtomo no Kuronushi.

Please note that Ōtomo no Kuronushi is not actually a gangster, but another of the 6 great waka poets of the Heian period. But in this play, he's out to get Munesada and his brother, and there's a conspiricy for him to kill both of them.

I have no idea why Kuronushi seems to have such a problem with everybody. I think his poems are pretty good! But most of the stories I know of him paint him as an extremely petty, jealous man. Perhaps the most famous is that in which he feuds with Ono no Komachi herself:

The two are set to enter a poetry competition for the Emperor. Kuronushi was nervous that Komachi's poem would be better, so he eavesdropped on her practicing and was astounded at how beautiful her poem was. Devising a plan, he went to the Manyōshū, the oldest and one of the most famous anthologies of Japanese poetry, and wrote her poem into the book. When Ono no Komachi recited her poem at the contest, Kuronushi accused her of plagiarism and produced his copy of the Manyōshū. Komachi, having none of this, asked for some water, and put the page into the bowl. The writing of the book remained, but the fresh ink where Kuronushi copied her poem washed off, and she won the competition, and Kuronushi was embarrassed before all.

Aren't Heian stories the best? Worst?

Anyway, this legendary rumour is often cited by Sekibei during his drunken rampage.

The letter to Munesada goes on to say that Kuronushi believed that Yasusada was in his brother, and will no longer be out to kill Munesada. Munesada, however, has found an heirloom of Kuronushi's family nearby, and believes that Kuronushi is wise to him and closer than the letter knows. He asks Ono no Komachi to go for help, and he retires to pray.

During his prayer, he also holds a memorial for his brother, and places the sleeve on the altar. Suddenly, Munesada realises that having the blood-stained garment in such a holy place is profane, and he has violated the purity of the temple. He quickly hides it in his koto as an even drunker Sekibei stumbles in. He questions Sekibei as to his intentions for insulting Komachi earlier, but Sekibei waves him off, grumbling and heading back to his post to drink more.

As he sips his sake, Sekibei sees the reflection of the stars in his bowl.

He notices the auspicious arrangement of the constellation, as well as its position in relevance to the planets, and realises that it is a sign that the time has come for him to enact his planned take over. He conspires to make incense out of the wood of the cherry tree, which will carry his motive. Sekibei rushes to fetch his axe, and relishes his evil plan with glee, revealing it to the audience like a Bond villain as he sharpens his weapon.

To test its might, he swings his axe at Munesada's koto, cleaving it in half. The bloody sleeve of Yasusada slips out, and the imperial seals which Sekibei carries fly out of his pocket and attach themselves to the cherry tree. Sekibei turns on the tree and regards it with suspicion, believing that a demon must be inside. He swings his axe again and tries to chop down the tree, but at once a branch strikes him and he finds that his body has gone numb.

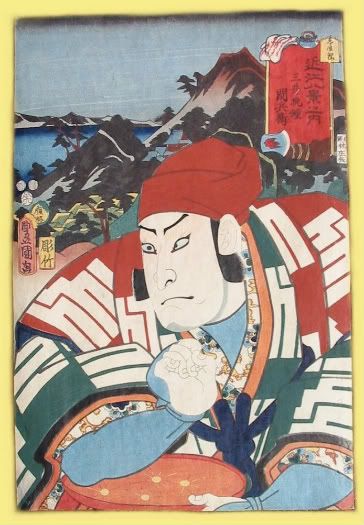

Very, very famous, as you can see.

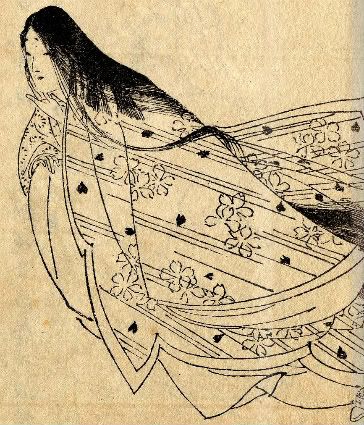

Unable to move, he stands frozen as the spirit of the cherry tree materializes into the form of a beautiful Oiran.

This Oiran is named Sumizome, and she was Yasusada's lover. She grips his bloody sleeve and sobs, relating her tale. When she first saw Yasusada, she fell deeply in love, and her spirit transformed her from a tree to a woman, so that she could be with him. She tells Sekibei that she heard his plan to take over and she plans to stop him, but first she must take revenge for Yasusada.

It is then that Sekibei regains control of himself and sweeps off his gatekeeper uniform, revealing himself to be... Ōtomo no Kuronushi!

DUN DUN DUNNNN

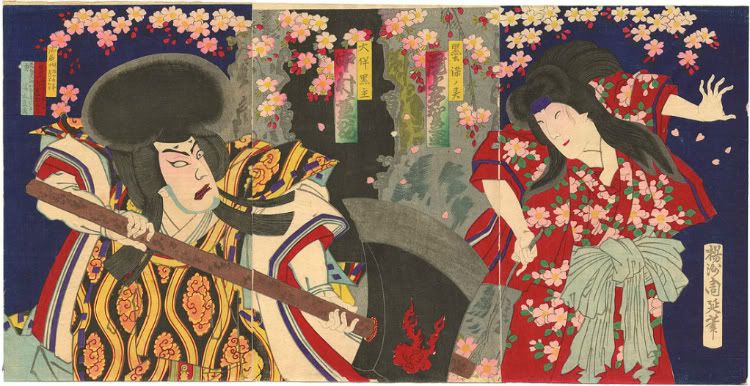

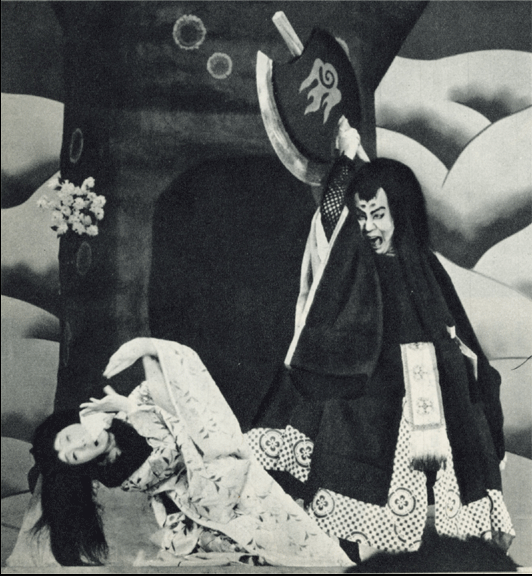

Kuronushi and the cherry tree's spirit have an epic battle, one of the best examples of stage-combat in all of kabuki.

The play ends with the pair still in mid-battle, but it is clear that Kuronushi is slowly losing.

So that's the story.

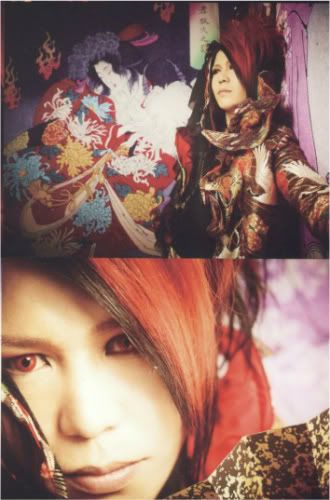

And now let's take a look at Isshi's interaction with the print.

He actually doesn't pose with this one as much, but we can still get some glimpses into his intention.

Obviously, the symbolism of the cherry tree, and all of the famous poets and Heian beauty it references would be appealing to Isshi. As well as the muted colours and the ghostly, sad-looking appearance of the cherry tree's spirit. They contrast heavily with the other two pictures, as well as Isshi's overall look. But he uses the soft purple colour and whirling cherry blossoms as a background several times.

Obviously this ties in closely with the often pastel, cherry-blossom motif of most of Kagrra's albums and backgrounds on stage.

I really like this, though. He stands beside her and looks off as if he can relate to the plight of the cherry blossom's spirit. But note the position of his hand brushing her kimono. He touches the back of her neck above the collar. Traditionally, this is very risqué. I don't want to be crass, but let's just say that, in the time of women in kimono, it was believed that to touch this area was the most erogenous zone on the female body.

As you saw in the last entry, and you'll see in the next one, since all of the prints depict women, Isshi often superimposes himself over them, or associates himself with them, or wishes the viewer to see him and the photo from the girl's point of view. I think it's a nice effect that he exhibits such an outrageous masculine gesture, subtle as it may be, when the picture is so overwhelmingly soft and feminine, and likened to his Heian poetry floweriness and female demon persona.

So why this one? It's actually quite famous. While some of the other ones from this series that I've shown before or will show in the future are pretty iconic, and there are several more than I was exposed to almost daily growing up, this particular piece, Okiku's ghost, and the Heron Girl are most prevalent to be seen around Japan.

I think the reasoning for this brings us to the core of Japanese art and aesthetics, which I've discussed here. The image of Komachi-zakura no Sei is so striking, especially for a Yoshitoshi print. The colours are extremely muted, and there's so much negative space around her. The main focus is this ghostly apparition, standing rather tree-like amidst nothingness, cherry blossoms whirling around her. It's so simple, a direct appeal to the Japanese sense of harmony, and spirit, which the cherry blossoms themselves represent.

I think that's why it was chosen to contrast so strikingly with the other two images in the photoset. And while some part of it may have been because of Isshi's interest in kabuki, Heian poetry, or even the author Ono no Komachi herself, the image is selected less for what it represents, and more for the cultural and visual appeal alone.

I must stress that Ono no Komachi's part is a bit part, since the kabuki is not one focusing on her lesson-in-restraint crone self, nor is it a dramatic interpretation of her many love affairs. The spirit of the Cherry Tree is only known as the spirit of Komachi's Cherry Tree since Ono no Komachi is meant to represent the transience of beauty, something at once heart-breakingly lovely, and then suddenly gone, scattered on the wind into nothingness, in the Buddhist ideal which alludes to life itself. It also lends this effect to cherry blossom trees, which is why they are the symbol of Japan, the Japanese spirit, and the symbol of Kagrra,.

Thank you to LiveJournal user sutafairu for providing the pamphlet scans, and please look forward for Part III, the final part, very soon!

No comments:

Post a Comment