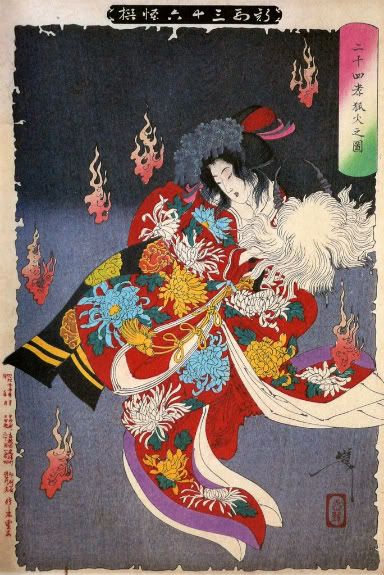

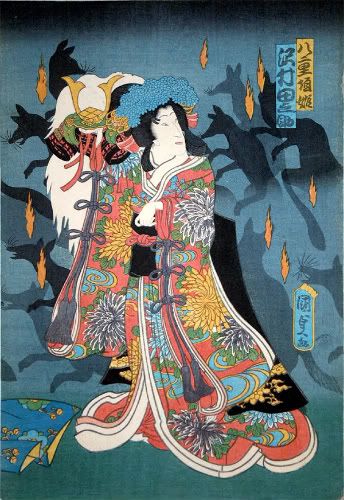

So let's interpret that one right in the middle, possibly the most famous of all three.

This is such an impressive picture. I translate it as "Fox-Fire from 24 Examples of Filial Piety". Oh, and she's Yaegakihime, FYI. So there's a bit to explain, I might as well start at the beginning.

Fox-Fire, what is that?

Literally kitsunebi (狐火, fox + fire), you may recall one of the most well-known yōkai in the West, the kitsune, which here means "fox spirit". I've talked a little about this before, but I'll give you a brief re-introduction. Originally drawn from the Chinese tales of bewitching women who were actually shape-shifters, and would lure a man before turning back into a fox, either as a prank or something more violent, the stories fit well in the Japanese paradigm of yōkai. Ever a popular motif, fox-women and their shape-shifting ilk are so well-known in Japan, they aren't even in the realms of yōkai anymore; kitsune are part of Japanese culture. There are so many famous stories, legends, and little anecdotes about kitsune and what they do, it becomes a superstition. Kitsune are tricksters, kitsune will lead you to your death, etc.

On the other side of the coin is the wise and revered kitsune, seen as a messenger to Inari. You might have eaten some Inarizushi or Inari udon, which features deep-fried tofu skin. It's said to be a favourite of the fox messengers of Inari, thus the name. The kami Inari is associated with rice, business, fertility, and agriculture, and therefore developed an enormous following, and is one of the major deities in Japan, with many shrines dedicated to Inari's worship. One of the most well-known shrines is the one with all of the red torii lined up...

Perhaps you've seen this one before? It's Inari's main shrine, located in Kyoto.

Inari is also linked to foxes, and the fox is a symbol of Inari. Many foxes will be prominently featured at Inari's shrines, statues and imagery signifying their assistance.

They have a creepy sort of stare that never leaves you.

These kitsune are thought of very highly, though sometimes they are still tricksters, but the many-tailed foxes (whose many tails signify their great age and wisdom) are thought to be those acolytes of Inari who have achieved supernatural powers.

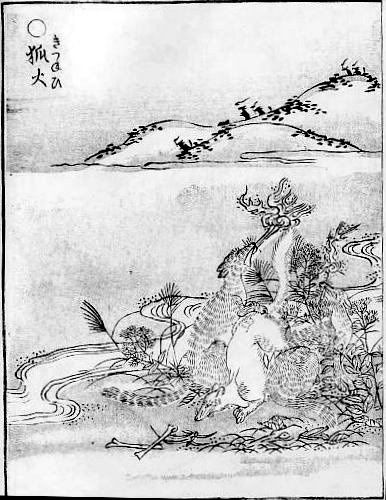

Many singular-tailed kitsune in addition are thought to possess the ability to summon iridescent light, or small fires, thus, the kitsunebi.

You find yourself walking along a road or path. It's night-time and there doesn't seem to be anyone around. Suddenly, a flash of fire springs up nearby, or flickers warmly in the woods. Perhaps it looks like someone's lantern. You can almost hear them calling for help. You go to investigate, and another fire sparks, another lantern appears farther away. You follow the dancing flames, cheerfully alluring, the lantern bobs away, but you keep after it: perhaps you can hear someone crying. They must be lost! But no, it is you who is lost, and now you are deep in the woods, or simply a dark cloudy area which may or may not be another plane of existence. Which way is down, which way is up? Another fire, another lantern, and you're surrounded... you keep chasing that flame, trying to find your way out, or else you suddenly find that each lantern is held firmly in the paw of a tall fox spirit, and they are surrounding you, and you never knew how many teeth foxes had...

It gets real bad, real fast, is what I'm saying.

The kitsune from the Obake Karuta.

But it's not always so ominous. Sometimes, you just hear little twittering sounds, and it hits you: you're being laughed at. By fox creatures. How embarrassing. Then you hang your head in shame and go home.

Sekien's kitsunebi

As for the servants of Inari, they are most often (though not always) depicted as slim white spirits with attractive pointed faces (watch out, girls who look like that are probably foxes! And not the good kind...) Inari messengers are there to help you. If you find yourself lost before the kitsunebi starts lighting up, they are most likely guiding you back to safety. In the olden times, it was said that, if one wanted to walk across a frozen lake, to wait and see if a fox will go across first, for they are smart and will know if it's safe to walk on, and may even be sent by Inari to lead you in the right direction (or alternatively are floating across and leading you to drown... foxes are tricky creatures, so it's usually up to you to notice if their aura seems nefarious or not). But most of the time, foxes of Inari are doing what they do best, not being too concerned with human affairs unless necessary. They keep the keys to the rice storage house, they deliver messages to other spirits, they make kitsunebi because it looks appealing and it's nice to dance around.

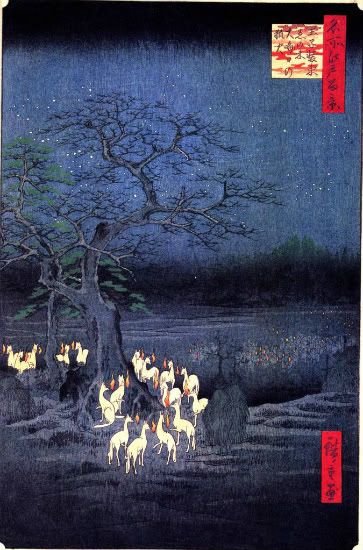

One of Hiroshige's prints from the very well-known series, 100 Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景), kitsune gather around a tree near the Oji-Inari Shrine on New Year's Eve, to celebrate and receive instruction for the upcoming year.

OK, so what next? 24 Examples of Filial Piety, then. Honcho Nijuushiko, 本朝廿四孝, is a collection of tales glorifying Confucian lessons of respect to one's parents. As a popular set of stories, naturally this was just the thing to be adapted for the Japanese theatre. But you know Japanese theatre: if it isn't calling reference to well-known historical figures or dramatising current affairs, it just isn't worth doing. So Honcho Nijuushiko's lessons were re-imagined to fit the famous feuding families of the Sengoku Period, the Takeda vs. the Uesugi.

Please know that, as I describe this tale to you, none of this actually happened. None of it. I will do a Sengoku Spotlight on the profoundly interesting daimyo Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, but keep in mind that neither man would be involved in such romantic intrigues as this play. It's so melodramatic, you guys.

So. This part is true. During the Sengoku jidai (Warring States Period) of Japan, two of the most successful early daimyo vying for control of the country were Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin. The two referred to one another as 宿敵, nemeses. They ruled over neighbouring provinces, and engaged in a series of battles almost annually, neither one making any leeway. Each prided himself on his skills as a strategist, and they found the other to be a match, irritating as it was. So this one would attack the other, then the other would attack, then they both would attack, lose some people, re-group their armies, and start all over again. Their rivalry and the uncanny way in which each would guess the other's move, one-up them, and then be one-upped by the other expecting that, is popularly depicted in many stories.

This story... eh.

Like Tsumoru Koi Yuki no Seki no To, Honcho Nijuushiko is a play which is also mostly well known for just the last bit, and popularly referred to as such. When most often performed, it's just the final two or three parts, or only one famous part, which are shown.

But originally this was written as a Bunraku, a puppet play, so I'll give you a brief synopsis of all the political and romantic intrigue that has happened before the ending scene wherein our print takes place.

The Ashikaga Shogun has conceived a child with his mistress, and many daimyo arrive to offer him gifts and congratulation. Among them are Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, here known by their former names, Takeda Harunobu and Nagao Kenshin. Several daimyo allude to the fact that it is well-known that the two cannot stand one another, and accuse them of trying to overthrow the Shogun. Everyone bickers for some time until a compromise is suggested by the Shogun's level-headed wife: Takeda's son Katsuyori will marry Nagao's daughter Yaegaki, and the two will be united and it will appease those who believe their strife will overthrow the Shogun. The clans agree.

Much court intrigue then takes place, wherein one of Nagao's retainers meets with his girlfriend, but it was actually a case of mistaken identity, because he accidentally confesses love to the Shogun's mistress! She says she loves him, though she knows who he is and who he was meaning to speak to, but if Ran has taught us anything, it's that Sengoku Period ladies are insane. The Shogun finds out and flies into a rage, trying to kill his mistress, but his level-headed wife stands up for her, and the mistress confesses that she had wanted to die because she felt terrible for conceiving a child before the Shogun's kind wife, and was only pretending to love the retainer. The mistress makes plans to become a Buddhist nun, and enter stage left is a scheming samurai who has come to gift the Shogun with a rifle.

Speaking of insane Sengoku Period ladies, it turns out that the samurai is actually Saito Dosan in disguise, the father of the most insane Sengoku lady of them all, Nobunaga's wife, who, in popular legend, was barren and married to him only to assassinate him on the orders of her wicked father: Nobunaga fed her false information about her father's generals and Dosan had them killed, letting Nobunaga know she was up to no good, and then she was never mentioned again. Dosan would later be killed in a coup by his own son, who was just as weak and wicked as he, and provided a much easier in for Nobunaga to come and take over the castle and the province.

Anyway, the Shogun asks the disguised Dosan how the gun works, to which Dosan manically replies "I will show you!" and shoots the Shogun with the rifle, killing him.

Ah, court intrigue. How confusing and popular you are.

The mistress is abducted, and Nagao Kenshin and Takeda Harunobu are accused of being behind the entire plot. Two daimyo make a pledge to the Shogun's wife to find the culprit within three years, or else they will kill their sons in repentance. Harunobu changes his name to Takeda Shingen, taking the Buddhist doctrine himself, in a way that did not in any circumstances unfold like that, and Kenshin pardons his retainer and sends him off with his actual girlfriend.

At this point, I'm going to butcher-edit this play, because it goes on for quite possibly hours of explanations with much mistaken identity and secret plots and such. Suffice it to say that no one is who they seem, everyone disguises himself as someone else, several key people end up being switched at birth, and hey man, I just wanted to see some puppets, come on now.

Yeah!

So three years pass, and the sons of Shingen and Kenshin must kill themselves in repentance for the promise their fathers made. Shingen's son, Katsuyori, is blind and in love with a lady-in-waiting, but he has to die, so he does so. But it turns out that Shingen's real son was actually switched at birth (!) by a retainer wishing to overthrow the Takeda and put his own son in Katsuyori's place. His crime is discovered and he is put to death, and the lady-in-waiting wishes to die too, now that her belovied fake Katsuyori is dead. The dying retainer tells her not to kill herself, and instead to recover Takeda Shingen's famous helmet, which is indeed so famous that in real life it is one of the most famous helmets in history, and a treasure associated with Takeda Shingen.

Whoa there, sir. That's almost too much badassery for just one picture.

In the play, Shingen's helmet had been blessed by the gods and was being kept safely at a temple. Apparently it was his helmet that gave him true power, and protected him in battle, and only the pure of heart could wield it. Kenshin discovered this and convinced one of the pages at the temple to smuggle it out, and stole the helmet for himself. Though he was not able to use it, at least Shingen couldn't use it in battle, either.

Meanwhile, the real Katsuyori has been living as a poor gardener. He discovers who he really is, but stays in disguise so that everyone will keep thinking that Katsuyori is dead. Kenshin's son disguises himself as a messenger ordering Kenshin to kill his son, but Saito Dosan catches wise to this plot having been masquerading nearby as a gardener named Sekibei (holy shit, nobody ever hire a gardener named Sekibei), and jumps out with a big "A-HA!" Kenshin recognises Sekibei as Dosan, and Sekibei's new assistant gardener as the real Katsuyori, but says nothing and sends "Sekibei" on a mission to report findings of the real killer of the Shogun, hoping that Dosan's effort will lead Kenshin to the clues he needs to accuse him.

Elsewhere, Lady Yaegaki (Yaegakihime, Kenshin's daughter), is mourning the news of Katsuyori's death. Even though they had never met, she had been engaged to him for three years, and had been looking forward to the marriage.

In another very well-known scene, Yaegakihime, sitting on the right side of the stage, lights incense for Katsuyori in front of a picture of him. The lady-in-waiting, on the left, weeps for her deceased boyfriend. Katsuyori the gardener, now dressed in fine clothes, appears in the center, and the two women rush to him, Yaegakihime recognising him from the photo, and the lady-in-waiting astonished at how much he looks like her dead lover.

Katsuyori feels sorry for both, but keeps up his disguise, and a long and flowery romance scene ensues wherein Yaegakihime tries to get him to admit to being her Katsuyori, and he keeps insisting he is only a poor gardener. Yaegakihime begs the lady-in-waiting to arrange for him to be with her, but Katsuyori stands firm. Yaegakihime promises that, if he will say he is Katsuyori and marry her, she will go and get him his father's helmet from where Kenshin has hidden it. He still refuses, at which point I think he is clearly insane. Yaegakihime is acting in an extremely forward and aggressive way, not at all the innocent and filial paragon of humility she is famous for. Yaegakihime feels humiliated that she was wrong, since she loved him so much she thought he must be her Katsuyori, and tries to kill herself. This happens a lot. Katsuyori realises that her brazen manner was brought on because she was so devoted to her father's wishes and lifelong devotion to her one true love that she was (somehow?) able to recognise him immediately. Sure, of course. Finally, he admits to being the real Katsuyori, and the two share a passionate moment.

Kenshin, lurking in wait of his own "A-HA!" moment, appears and instructs the "gardener" to deliver a message to a town on the other side of Lake Suwa as quickly as he can. He then summons his two strongest retainers and sends them to ambush and kill Katsuyori.

That part is popularly told as a set-up to the final scene, Kitsunebi.

Yes, all of that, as trimmed-down as I could get it, was just to get to this one scene. But, as is the case in most kabuki, you don't go to see the story. Without the set-up, the play will make approximately zero sense, but it's not supposed to. During the Edo period, everyone knew the story, or was expected to after the initial full performance. You went to see the kabuki to see how this theatre portrayed it, what this actor's method was like, how expensive the costumes and set-pieces were. So, though I usually ramble, this time, it was for a purpose. Most kabuki will be completely confusing and nonsensical if you don't intimately know the story, which, clearly nobody really does anymore. So the theatres will give out pamphlets detailing the intricacies of the plot which will have bearing in the "main" act or particular selection, and the nicest ones will even give you little headphones with which to listen to an elderly man drone on about the subtlety and nuance of each scene, and the flowery and unnecessary history behind every single movement ever.

Yes, I will probably freelance myself as old droning kabuki narrator once my voice matures to the appropriate disturbingly ancient sound.

So Honcho Nijuushiko generally refers to the last act which is called Kitsunebi, or the last few acts, usually beginning at the garden scene (Jusshuko) where Katsuyori is revealed.

Yaegakihime learns of the plot to assassinate Katsuyori, and runs out into the snow to warn him. Unfortunately, he is already gone, and she is afraid of crossing the frozen lake and unable to reach him. Not knowing what to do, she goes to a shrine to pray. After a moment, a flash of fire appears, and Yaegakihime approaches the edge of the frozen lake, peering down onto the ice. She sees a reflection, but instead of her own face, it is that of a white fox.

Several white foxes appear and move around her, and one crosses over the ice. Knowing that the lake is safe, she retrieves Takeda Shingen's famous helmet, and holds it high aloft as proof of the two clans' unity. The protective god's spirit recognises Yaegakihime's pure soul and possesses her, allowing her to fly across the frozen river. Accompanied by a pair of white foxes, Yaegakihime follows the fox-fires across to the other side, and to Katsuyori.

It's such a moving scene, and the intricate dance itself, as she is possessed by a fox spirit which guides her across the lake, is one of the best examples of the kabuki style.

Please watch this video of a bit of a performance.

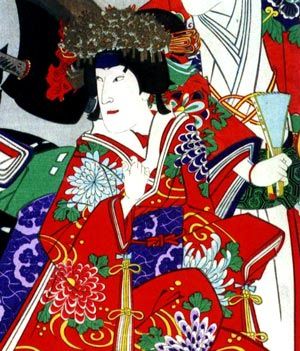

As you've seen, most famous characters in kabuki have a very particular style, pattern, or accessory to their costume which signifies them as that character. It can be manipulated for aesthetic or unique purposes, but generally there will be some element of the design which makes sure the casual observer can identify it.

So imagine that you haven't actually read anything that I've written until this point. (Perhaps you don't need to imagine...) I will tell you exactly what you need to look for in order to identify Yaegakihime ten times out of ten. That way you, like me, can impress others by seeing a split-second clip of an actor readying himself for a performance and smugly inform your friends that he is playing Yaegakihime in Honcho Nijuushiko. They will be very impressed. This is the positive side to kabuki not being so well-known anymore. Even the smallest detail will be extremely obvious with the slightest bit of inside information. Besides, this is so famous that, more often than not, if you see an onnagata in a kabuki promotion or performance still, he has or most likely will be portraying Yaegakihime.

First up is her head thingy. This head thingy is called a fukiwa, which refers to the specific wig type used by kabuki actors (and doll-makers) for a role like Yaegakihime. It has a big drum in the back, which is covered by a crown of silver hana-kanzashi, hair pins like bunches of flowers. This particular look is nearly specific to Yaegakihime.

Most importantly is the uchikake, the heavy outer robe. In my experience, when most people think about kabuki, they picture the female character wearing this bright red uchikake. Actually, it's not as common as you would think. The red uchikake and furisode (long-sleeved kimono worn by young girls) are usually worn by akahime (red princesses). There are three famous akahime, one of which is, of course, Yaegakihime. So while you may see many akahime, it isn't that they're in every play, it's just that they're in the most famous ones they do over and over again.

The akahime roles are famous, but also difficult. For an onnagata to be chosen to play such an important role, he must have mastered not only the guise of a woman, but a very emotional and devoted performance of the younger girl as well. Outside of kabuki, red uchikake are most often seen at weddings, covered with embroidered symbols of good fortune. This comes from Buddhism, where red is a very lucky and auspicious colour that denotes innocence and purity. So these female roles of Buddhist valor require that the onnagata completely devote himself to the character, a demanding performance. It is the highest honour for an onnagata to master the many gestures, movements, and even voice pitch of the young girl in kabuki. This is why so many people will want to go see those famous plays, because it really requires a good actor, a talent which isn't always appreciated as it should be nowadays. So to see a man give a traditional performance in an impossibly expensive bright red uchikake, you would expect that he is among the very best.

You would expect it, I said.

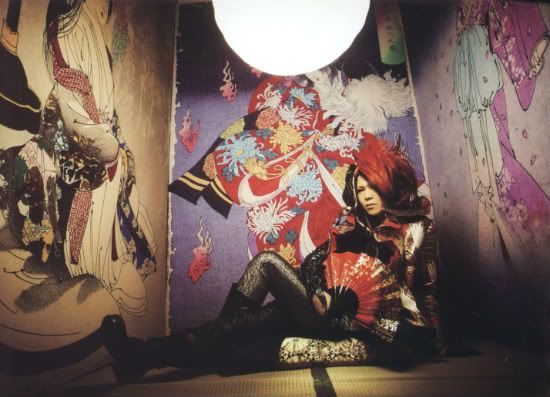

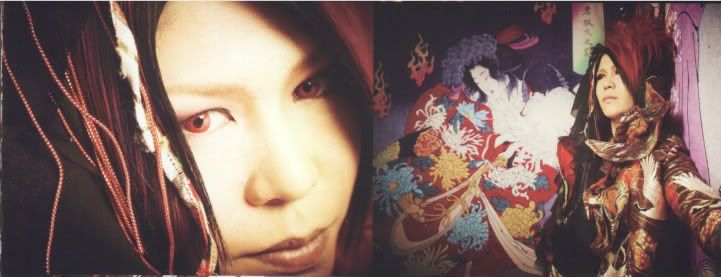

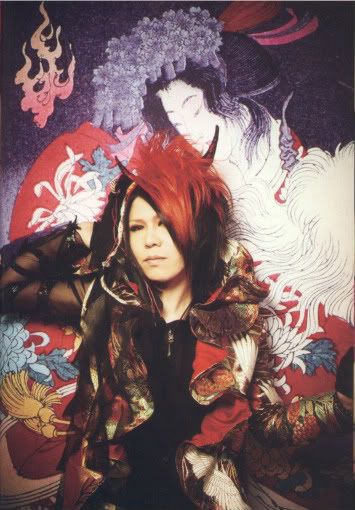

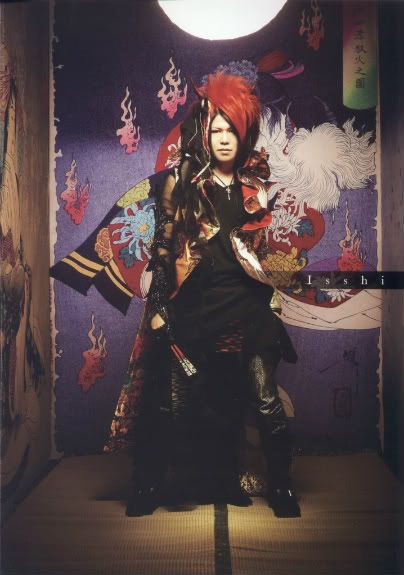

So, let's look at a few more images from this story and see if we can figure out why Isshi chose this one.

I like that it's a famous example of bunraku. Traditional Japanese theatre is usually thought of as kabuki, and then Noh, and bunraku is often forgotten. Bunraku is also extremely difficult to pull off (I've actually seen some that I and many others have classified as bad bunraku, it is not only possible but extremely obvious when done incorrectly). Also, the puppets are very disturbingly real. You wouldn't expect it, but you can even mistake a long-shot of bunraku for live action. Puppets are disturbing things.

There are quite literally hundreds more depicting just that one scene from the kabuki, and glorifying the wonders of the theatres and onnagata who play Yaegakihime, but suffice it to say they're all quite good and, well, similar. Let's see something different.

This is a statue of Yaegakihime holding Shingen's helmet, and as you can see, it is located on the lake where the story is meant to have happened. Takeda Shingen was lord of Kai, and expanded his territory into Shinano Province. When I do an entry about Shingen and Kenshin, I will discuss the significance of location that plagued the two throughout their lives, but now this statue stands in present-day Shinano, Nagano Prefecture, just an hour away from where Isshi was born.

As you can see, he mostly stands in front of or near the print, and doesn't interact with it as much in the way he did with the other two. And he doesn't really need to. The details of Yaegakihime's clothing is enough for an good photo, with all of her layers and colours clashing or blending with all of Isshi's. The vibrant colours in both costumes are amazing, and the interesting form and movement of Yoshitoshi's work coupled with the way Isshi poses around it to incorporate interesting angles and contrasts is quite different than what you usually see in a "normal" J-rock photoset.

But like I said, all of this is completely my own interpretation of the pictures, and it's extremely possible or even likely that I'm horribly wrong, but from what I know of Isshi, and his constant purpose in song, interviews and videos to incorporate traditional Japanese things and not explain them, to insist that the fan becomes interested and tries to learn and spread the culture on his own by the prompting of Kagrra,'s music, this is what I have come up with. I suspected that it was Isshi who was the Yoshitoshi fan since Kotodama, and while the outfit and the poses and the pictures may have been completely out of his hands and done for him, I have to think that, this being his very final photoset with Kagrra,, given to lifelong fans during their final tour, he must have had some say in the look and thoughts he wanted to convey, and it has a bit more significance than just another photoset from just another band.

In the very first Kagrra, PV I ever saw, Kotodama, all of the Yoshitoshi images were visceral and shocking, underlining the scary theme of the video, and sending a message of demons in their rawest form. Here, we see ghosts and demons as well, but the look and stories behind them are so much more pure and calm and universal. Though they all contain Buddhist elements, Buddhism in Japan is heavily mixed with all other Japanese beliefs and ideas, and honestly, the overall feeling from this shoot, like most of Kagrra,'s things, is just a Japanese feeling. These images are Kagrra's favourite description of themselves, 和 (wa), harmonious, or, simply the core of what it is to be Japanese.

And before you get carried away by the peaceful beautiful ghosts of traditional Japan, here is Isshi, dressed as he has been since the beginning, in the guise of a female demon, following the messages of the gods.

No comments:

Post a Comment