When the blanket of unbearable humidity descended upon my house, and the overwhelming heat knocked everybody to the ground, houses would put out streamers and wind-chimes that caught the smallest, slightest breeze so that just seeing them made you feel a little bit cooler, even if physically it was still hot.

One of my favourite parts in Ōkami was when you had to do the wind brushstroke and make all of the carp streamers wave so you could jump across them. It was very relaxing and cooling, and less invasive than suffering through 100 Ghost Story Night in a vain attempt to summon some "spine chills."

In mountain villages, for example like the one I lived in when I was small, people would hang carp streamers all around in honour of Boy's Day. I'm now always nostalgic for towns decorated for festivals, and Boy's Day was probably my favourite because of the awesome things boys would get to do on this day.

Of course, Boy's Day, or Tango no Sekku (端午の節句) was held on 5/5, a response to Girl's Day, or Hinamatsuri (雛祭り) on 3/3. Boy's Day marks the first day of summer, and is signified by a number of manly decorations I'll describe shortly, to counterbalance the absurd rituals of Girl's Day. Even though Boy's Day is now called Children's Day (こどもの日) instead, most Japanese still basically consider it Boy's Day, and tell the stories and do activities for the sons in the house who were forced against their will to participate at the Hinamatsuri amongst the creepy dolls.

That's just too much.

Girls would be paraded about as little Heian princesses, and boys would have to wear fancy pants and be nice to any girls they encounter even though clearly at that age they are all icky. But even though we must now call Boy's Day Children's Day, the celebrations remain.

My friend called me to come pick her up after the traditional event her club had that morning. I arrived and began the excruciating clean-up process, accumulating a fine number of blisters on my hands, and panting in the heat from the manual labour I had to do. Thankfully, there was a tsukubai set on a rock where I was obliged to wash my hands and mouth.

It was then I caught sight of these:

Carp streamers! Koinobori (鯉幟) are hung to represent the boys of the family. Generally there are three carp per streamer for the parents and son, and smaller ones can be added for additional boys in the family. You can see by the photo that there really was no breeze. At all.

So why carp? Koi fish represent power and strength, because of the tendency of carp to swim upstream. It's actually tied into a Chinese folktale, which is why the carp are swimming through the sky instead of water.

Of all the animals in the Chinese zodiac, the only one we don't actually have proof of is the dragon. But if you look at Chinese paintings of dragons, they are always depicted as being surrounded by clouds. This is because the sound of thunder is actually a dragon's breathing, and dragon's breath causes clouds. So why we don't see dragons along with the other zodiac animals is because dragons live in the sky. Dragons are famous for their power and are often shown clutching a jewel. Dragons and people born in the year of the dragon are known for their personalities to strive for greatness and attempt to achieve the impossible. Coincidentally, this year, 2012, is the year of the Dragon.

So in China, and now in Japan as well, we see the carp swimming upstream, trying to achieve the impossible. This is because, when a carp is finally able to jump his way to the very top of the stream, he will become a dragon. And the carp streamers, of carp flying proudly in the sky, represent nobility and strength, and remind boys that they are on their way to achieving success.

And yet even the carp are no match for Kintarō.

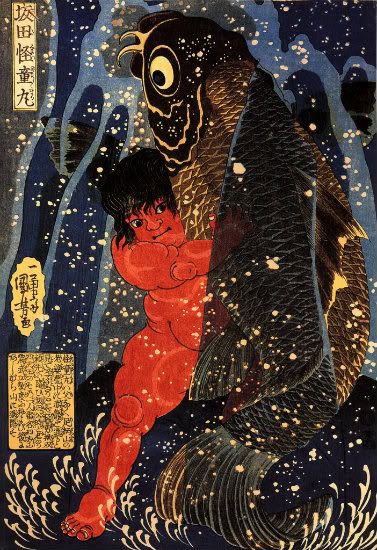

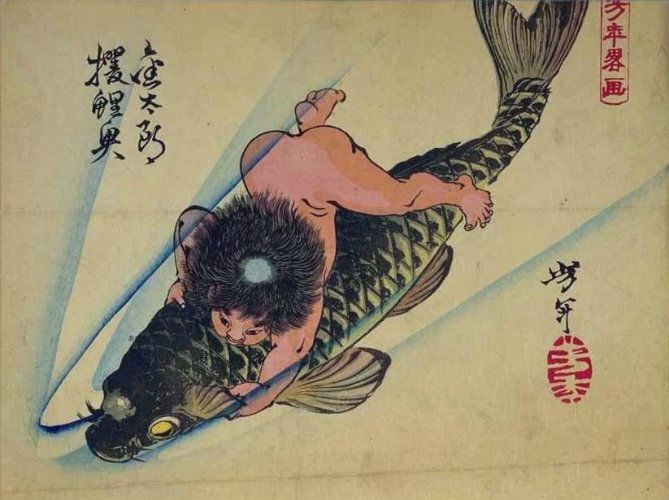

Legendary child of Japanese folktales, Kintarō has a great number of stories describing his feats of awesomeness. He was apparently conceived when a mighty dragon roared and the force of the thunder impregnated a yamanba (mountain hag yōkai), who gave birth to Kintarō. He lived in the mountains like a feral creature, fat and red and never without his trusty axe, often depicted, kappa-like, underwater with a little pool of water resting atop his head.

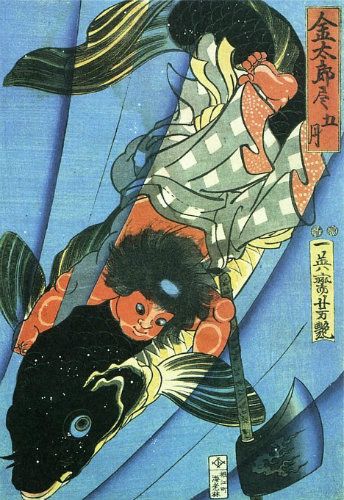

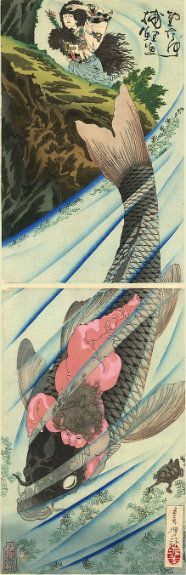

He would push over trees, break boulders, and had the power to command animals and village children alike. Many ukiyo-e show him refereeing wrestling matches between different animals. But he's quite famous for a wrestling match of his own.

An enormous carp was terrorizing the rivers of Kintarō's mountain, and not like Hanako, the 200+ year old carp who swam around being great.

She was great.

But this was a monstrous carp, so Kintarō's animal friends enlisted him to save them from the beast. So Kintarō dove right into the river and beat the crap of out the carp.

Can't have an ukiyo-e post without some Yoshitoshi.

Here, have more.

Kintarō vs. Carp came to symbolise the power and strength, not only of carp, but of little boys, too. Kintarō grew up to be a Heian aristocrat and act as retainer to a Fujiwara lord, and it was said that he didn't ride on a horse like the rest of the men, but a bear. Amazing.

So this is what I was thinking about as I finished cleaning and went to meet my friend's traditional group. She introduced me to the ladies, most of them old enough to be her mother or grandmother, the lot of them wearing nice summer kimono for their private event. This was when I realised that I had fallen in line with a group of contemporarily-dressed Japanese men, standing awkwardly amongst ourselves, friends and relatives of all the traditional ladies. Fantastic. Luckily, some of the women had brought their young sons along, so it didn't become my Boy's Day celebration.

They brought ice-cream and big koinobori. All of the males sang a song about the carp streamers, but there was still no breeze, so we just waved it around ourselves.

Then everyone sat and admired the kabuto samurai doll. While Girl's Day has an abundance of hina dolls, families with sons usually put out a samurai armour doll for the sons on Boy's Day. A single warrior doll or even a Kintarō doll will be displayed in the home, accompanied by sword and bow and arrow, to provide boys with an image of manliness and warrior strength that we should aspire to.

There also was a flower arrangement featuring an iris, or shōbu, which is associated with Boy's Day, because the shape of the flower resembles a sword, and the petals prevent illness if ingested or bathed in. Most importantly, the kanji for shōbu can be spelled differently to mean "warrior spirit" and "striving for greatness." You simply cannot have any sort of Japanese anything if there is not a pun involved, damn it.

One of the ladies then recited a poem which took for its first line each of the kana for shōbu, and told some story about romance and loss, and to be honest, I wasn't listening because I was eating an ice-cream. Another of the women asked if anybody else knew any other stories, and my friend suggested we all begin a 100 Ghost Story event to cool ourselves down. This was met pleasantly by some of the women closer to her age, and cringed at by a few of the husbands and older ladies. I gathered my courage, avoided my friend's eyes, and asked,

"Has anyone told the story of Kintarō yet?" Everyone looked at each other and asked "Who? What are you talking about?" I sheepishly explained that he was a famous boy associated with Boy's Day and all the carp, and kind of trailed off. The subject was almost dropped until the senior member of the group said "Yes, Little Kintarō who fought the carp and rode a bear into the Heian capital."

Many of the ladies pinched their sons and went on about how proud they were that some boys still took an interest in traditions, and my friend was properly mortified that she wasn't the most outstandingly traditional person there.

I was then compelled to tell the story of Kintarō, in my awkward and distracted way. How was it?

You said here that the Yamanba is the one who gave birth to Kintarō, but the oh-so-trustworthy wikipedia said th`t the Yamanba only raise him, at least on this article >> http://bit.ly/3l5kAD

ReplyDeleteOh, and I also feel sorry for the lack of breeze there. Really.

There are many different versions of Kintarō's legendary life, as he is a folk figure, and each region most likely has their own unique story. I've also heard that he was the son of an Empress and was kidnapped, and that he was part bear or demon or some other sort of thing. I chose the version I used here since it was the one I had heard most often growing up, as well as that it tied into the dragon motif I also discussed. Yamanba has a wide variety of tales about her (them?) also.

Delete